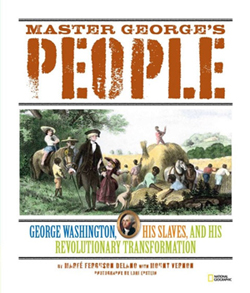

The government is shut down, but Mount Vernon is open, so it seems like a fine time to focus on a book about George Washington, whose estate is front and center in Marfé Ferguson Delano’s Master George’s People: George Washington, His Slaves, and His Revolutionary Transformation. As the title suggests, the National Geographic book examine’s Washington’s changing attitudes toward slavery — from growing up in a slave-owning family, to his own use of enslaved people at Mount Vernon, to commanding black troops during the Revolutionary War, and to his final will, which freed the enslaved human beings he called his “people.” The book introduces us to those people as well.

I feel lucky to have seen this book in its formative stages as Marfé, the author, is a member of my writing group. She has a critical eye that is at once sharp and gentle. She also has the world’s best speaking voice, and should consider a second career in audio books. Really. Her nonfiction includes Helen’s Eyes: A Photobiography of Annie Sullivan, Helen Keller’s Teacher and Earth in the Hot Seat: Bulletins from a Warming World.

I feel lucky to have seen this book in its formative stages as Marfé, the author, is a member of my writing group. She has a critical eye that is at once sharp and gentle. She also has the world’s best speaking voice, and should consider a second career in audio books. Really. Her nonfiction includes Helen’s Eyes: A Photobiography of Annie Sullivan, Helen Keller’s Teacher and Earth in the Hot Seat: Bulletins from a Warming World.

Me: Let’s start out with that deceptively simple question: What made you decide to write this book?

Marfé: I got the first glimmer of the idea for this book about 6 or 7 years ago, when a writer friend of mine mentioned that she was working on a historical fiction novel based on a proud, outspoken woman named Charlotte, who was a slave at Mount Vernon, George Washington’s Virginia plantation.

I was intrigued by Charlotte’s story, and my nonfiction radar started to hum. I wondered if there were any other interesting stories about George Washington’s slaves. Frankly, it was one of the first times I’d even thought very much about Washington having slaves, despite the fact that I lived only about 5 miles down the road from Mount Vernon. When I was in school, in the 1960s and 70s, mostly in the south, I don’t recall being taught anything about the Founding Fathers and slavery. It’s like slavery wasn’t even mentioned until it was time for the Civil War unit.

But I tucked that idea away while I continued to work on another project. Then a year or so later Mount Vernon unveiled a new exhibit, a tiny log cabin modeled on those that housed the slaves who toiled in the fields on George Washington’s outlying farms. I went to see it. And then I really started to wonder about these enslaved men, women, and children. Washington often called them his “people,” but by law they were his property. I also began to ponder the irony of the fact that the man who led the American struggle for “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness” held hundreds of people in bondage.

My curiosity led me back to Mount Vernon again and again (I can bike there from my house). I talked with Mary Thompson, a research historian at Mount Vernon, and she pointed me toward some sources. The more reading I did, the more details I learned about the lives of individual slaves, the more passionate I felt about this topic. Some of their stories were heart-wrenching. For example, after George Washington married Martha Custis, she and her four-year-old son and three-year-old daughter moved to Mount Vernon from southern Virginia. Martha’s children each brought their own personal slaves, who were children themselves. These enslaved children would have had to leave their own families behind. Surely the separation was painful.

Eventually I knew I wanted to tell the story of Washington’s “people,” of Caroline and Charlotte, Davy and Frank Lee, Christopher Sheels and more.

Then I did some research to see if there were any nonfiction children’s books on the market that focused on Washington as a slave owner. I didn’t find any. Aha, I thought! So I worked up a proposal and sent it to my editor, and she was very enthusiastic about the project.

Me: How long did it take and why do you think it took that long?

Me: How long did it take and why do you think it took that long?

Marfé: Well, one reason it took me so long is that I got so caught up in the research. Also, once I began pulling all my notes together, I struggled for a while with the structure of the book. I knew I only had about 10,000 words to tell the story, but there was so much I wanted to tell. And as my editor helped me to see, I needed to tell two stories in the book. One was the story of what life was like for the enslaved people at Mount Vernon. The other was the story of how Washington’s attitude toward slavery changed over time. So I spent a lot of time figuring out how to interweave these two things. Also, I found it daunting to tackle an icon, specifically in the context of slavery, which is such a powerful and sensitive issue. For a while I just froze up. Finally I screwed up my courage and plunged in. I should also say that I’m a slow writer to begin with. Slow, and easily distracted.

Me: While you were doing the actual writing, what was your biggest challenge?

Balancing the story of Washington’s life with that of Mount Vernon’s enslaved people.

Me: How much time did you spend at Mount Vernon?

Marfé: Over the 6 years I worked on the book, I went there dozens of times.I tended to return to Mount Vernon whenever I got stuck in the writing. I would roam the grounds or gardens or outbuildings, or visit the reconstructed slave quarters, and try to imagine what it must have been like there some 230 years ago. It was very powerful to know I was treading the same paths that Washington and his slaves walked. I always returned to my desk reenergized.

Me: Favorite spot there?

Marfé: The upper gardens.

Me: How did you go about doing your all-consuming research?

Marfé: I started out in Mount Vernon’s research library, but I relied most heavily on primary sources—such as Washington’s letters, financial records, and diaries—that are available online. In particular I relied on the digital edition of the Papers of George Washington published by the University of Virginia Press, and also on the George Washington Papers at the Library of Congress. I also consulted quite a few secondary sources. Plus Mary Thompson at Mount Vernon generously shared her own unpublished research with me. I also want to recognize her, and also Professor Edna Greene Medford at Howard University, for vetting the finished manuscript.

Me: In Virginia, too, where I grew up, it seems like we mostly glossed over slavery when it came to the presidents. I’m glad the time has come where we can discuss it in a more open fashion.

Marfé: Agreed. I don’t think slavery was even mentioned in relation to the Founding Fathers back when I was in school. But I think it’s important that kids understand that the FFs weren’t perfect, that they were complicated and flawed, just like people today.

Me: With all of that research, I have to ask: what was the most interesting thing you found out about George Washington that you DIDN’T include in the book?

Marfé: Before the Revolution, Washington seems to have taken communion in church regularly. But after the Revolution—after he began to consider slavery morally wrong—he apparently never again took communion. Some scholars suggest that this may have been because one is not supposed to take communion if you are committing an ongoing sin, and Washington considered being a slave owner such a sin.

Me: If you would, talk a little about Washington’s transformation.

Marfé: Like other people of his time, as a boy Washington accepted slavery as a fact of life. As a young man he was very ambitious, wanted to build a top notch plantation and become very rich, and in the economy of his time and place, that meant he needed land and slaves to work that land. He bought and sold slaves without a second thought.

But during the Revolution, his attitude toward slavery started to change. He decided he would not break up families by selling them, and he told his managers to put away their whips. He became increasingly troubled by slavery. On the one hand he depended on slave labor to support his wealthy lifestyle. He still saw his slaves as valuable property. He still expected them to work hard in exchange for the food, clothing, and shelter he provided. On the other hand he was increasingly aware that it was unjust. He began to explore ways to emancipate his slaves, but nothing came of it. Only in his will did he finally decide to reject slavery.

Me: Why do you think telling this story is important?

Marfé: I think it’s important for kids to understand that a person can be rightly honored as a hero, and yet not be perfect. I think most textbooks shy away from the story of the Founders as slave owners, but that contradiction is a fundamental part of American history, and it’s a story that needs to be told.

Me: I know that when I work on fiction, the characters move in with me for a while. Is the same true with nonfiction?

Marfé: Oh yes. It gets to the point where I talk about the characters as if they are daily acquaintances, and I can’t stop sharing stories about them with my family.

Me: Which do you find easier: Fiction or nonfiction? Why?

Marfé: Well, so far most of my writing has been nonfiction. And I find that hard enough. I’ve tried fiction a few times, and in some ways it seems like floating off into outer space, which is rather terrifying, considering I usually have cold hard facts to keep me tethered to Earth. I think I have to learn to trust myself and enjoy the voyage.

Your book came out in January, on Elvis’ birthday. Coincidence?

Marfé: Well, I was born in Memphis and my family has connections to the King…

Me: Wait. What???

Marfé: My Uncle Bob Ferguson (my dad’s younger brother) and Elvis graduated from high school in Memphis the same year (1953), although they attended different schools. Uncle Bob first met Elvis the next year, when he and his buddies went to hear Elvis at a small night club in Memphis called the Eagle’s Nest. Some of his pals started to frag Elvis a little, and when Elvis was on the dance floor between sets, they kept bumping into him on purpose, stepping on his toes. According to Bob, Elvis was unfailing polite, just kept saying “Excuse me.” They couldn’t rile him. So they realized he was a good guy. Uncle Bob went on to become a police officer, and his duties sometimes brought him around Elvis. A bunch of his friends moonlighted on Elvis’s security detail when Elvis become famous. Apparently Elvis loved hanging out with cops. Anyway, the year Elvis died my uncle started doing video interviews of all his fellow officers who had had a personal connection with Elvis, and eventually he shaped those interviews into his book called ELVIS: IN THE BEAT OF THE NIGHT: TRUE STORIES OF ELVIS AND HIS POLICE BUDDIES.

Me: Your favorite president:

Marfé: Abraham Lincoln, with GW a close second.

Me: Favorite thing to do when you have a free half an hour?

Marfé: Besides reading? The crossword puzzle. Or walking my dog 🙂

Me: I always like to ask people about their secret talents. For instance: Kathy Erskine is good at making dinner from whatever ingredients she can find in the fridge. Wendy Shang is good at finding things that other people lose.

Marfé: I can sightread piano music–although that doesn’t mean my fingers always hit the right notes!

To learn more about Marfé, please visit her online at marfebooks.com.

Agreed!

I have this book!! It’s fabulous!!

Oh, that’s great! I am going to booktalk it to our librarian =) Thanks so much for reading!

I loved this book–just booktalked it to my fifth graders. Great interview!

We are privileged to know you as well!

Wonderful, informative conversation between two amazing authors that I’m privileged to know. Kudos to Marfe for writing an amazing book!

Same here!

Thanks. There are definitely some things here I’ve never thought about before!