Author Beth Macy

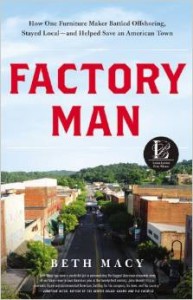

I’m button-popping proud to present journalist Beth Macy, whose new book Factory Man: How One Furniture Maker Battled Offshoring, Stayed Local — and Helped Save an American Town, comes out today. It’s a story of family, feuding, grit, gumption, pride, war and furniture. The book, which has been getting rave reviews, is Beth’s first, but you can bet the farm that it won’t be her last.

Me: As a newspaper reporter, you’ve done in-depth stories before, but you’ve never gone in depth to the tune of 582 pages. Aside from the obvious word-count difference, what are some of the differences between this type of journalism and daily newspaper journalism?

Beth: The planning was the biggest undertaking — and by that I mean the three months it took me and my agent to get the book proposal, including a 27-chapter outline, into shape before submitting it to publishers. I followed that loose outline religiously, though some of the facts changed as my reporting turned up new details and twists. Having the rough outline storyboarded like that afforded me the opportunity to focus close-in on the chapter I was working on at the time, which was freeing. I had the entire outline written on Wizard Wall (office supply nerd alert!) on an entire wall of my office. And I kept a white board next to my desk with notes for the chapter I was working on, plus a column on the left for ideas that came to me for the subsequent chapter. Between digital documents (interview notes, copious e-mails and court-case archives) and paper documents (in books, magazine and newspaper articles), I probably had 1,000+ different sources to comb through. Command-F on my iMac desktop was a constant companion; it was hard to remember what I’d named all my files. I need a better system for my next book!

Beth: The planning was the biggest undertaking — and by that I mean the three months it took me and my agent to get the book proposal, including a 27-chapter outline, into shape before submitting it to publishers. I followed that loose outline religiously, though some of the facts changed as my reporting turned up new details and twists. Having the rough outline storyboarded like that afforded me the opportunity to focus close-in on the chapter I was working on at the time, which was freeing. I had the entire outline written on Wizard Wall (office supply nerd alert!) on an entire wall of my office. And I kept a white board next to my desk with notes for the chapter I was working on, plus a column on the left for ideas that came to me for the subsequent chapter. Between digital documents (interview notes, copious e-mails and court-case archives) and paper documents (in books, magazine and newspaper articles), I probably had 1,000+ different sources to comb through. Command-F on my iMac desktop was a constant companion; it was hard to remember what I’d named all my files. I need a better system for my next book!

Me: I’ll ask a similar question about cultivating sources: I recall your saying you’d talked to John Basset III (the chairman of Vaughan-Bassett Furniture Co. and the book’s central character) more than 300 times on the phone alone. What was it like to go back to him that many times?

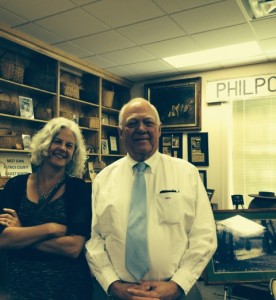

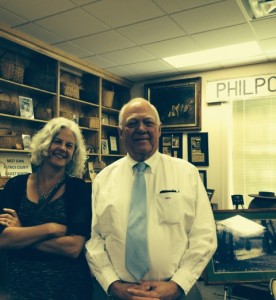

Beth with JBIII -- still speaking.

Beth: This is a hilarious question because I maybe called him five times out of the 300. It was — just about all of our communication — very much on his time: nights, weekends, daytime. Whenever he felt like calling me, he did. This entitled sense of timing is a huge part of his personality, though, and I was able to understand it better as I personally experienced it. I kept a list of questions I needed to ask him handy because I knew that usually a day wouldn’t pass before he’d call me again. We visited in person maybe a dozen times, including at his home and his factory.

Me: Did you ever have a point during the publishing process where you thought: This just isn’t going to happen?

Beth: No. Funny thing about an advance: They pay you, and you have to produce — or else you have to give it back, and that’s a very productivity-inspiring thing! I knew I had the bones of the story going in because I’d already written a pretty extensive 5,000 word newspaper article on JBIII. The more interviews I did and the deeper it went, the story just got richer and richer, and I became more excited about the material. I was overwhelmed at times by the scope of it — try to cover 110 years, with business practices spanning the globe — but mostly the more I learned, the juicier it got.

Me: What was the most difficult hurdle in writing this book?

Beth: Getting the CEOs who’d closed factories to talk to me. Most of them said no, including (initially) Rob Spilman of Bassett Furniture. I’d seen this great interview with George Packer on The Daily Show after his amazing book, “The Unwinding,” came out last year. And he actually made a quip about not wanting to talk to the CEOs in his book because he didn’t want them to become human to him. I thought, Amen! Then one of my best friends, a reporter visiting from Boston, convinced me that I needed to lay out all my cards with Spilman and convince him to talk. Because the book was as much, maybe even more, about what happened to Bassett, Va., as to Galax, and if I wanted to be fair and nuanced then I needed Rob’s perspective. He had a story to tell, too, and she advised being as transparent with him as possible about what I was trying to do.

A relative eventually intervened on my behalf, and I asked Rob a fourth (or whatever it was) time, and he finally relented to two lengthy interviews and several fact-checking sessions by phone and e-mail. He ended up giving me some of the best material in the book — including hilariously damning anecdotes about his father (stabbing the suckling pig and shouting “Larry Moh!”), poignant scenes about the closures, and important insights behind the company’s major shift to retail when imports hit and the factories closed. I’m grateful to him for talking to me, but I don’t expect he’s going to embrace the book because he believes the people and the town need to move on from the losses and not “sit around and cry in our beer.”

But a lot of people I talked to aren’t yet ready to move on from the losses. Many are still hurting, still looking for work. To move on, those losses first need to be acknowledged.

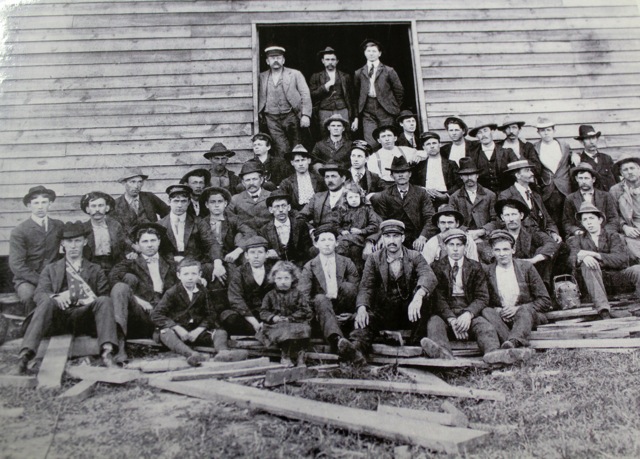

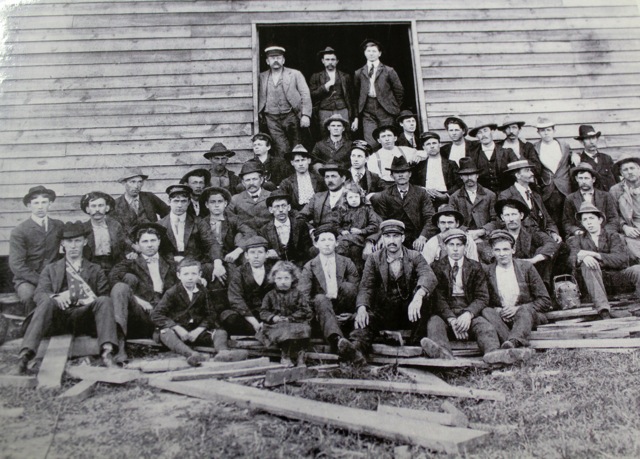

"The first known photo of Bassett Furniture Industries, circa 1902, wherein a wily saw miller named J.D. Bassett Sr. and his brother set out to swipe furniture-making from Michigan and New York and turn all that Reconstruction-era cheap labor and free trees into a furniture-making dynasty." (Quotes from Beth Macy)

Me: Has your research for Factory Man changed your shopping habits at all? In what way?

Beth: Our dishwasher broke last year, and when we finally got around to replacing it, we researched our options and chose a Maytag replacement because it was made in a Kentucky factory and was exactly what we wanted. (The price was comparable to the imports.) I go out of my way, buying clothes, to shop at local boutiques that carry made-in-America items, and I always thank the owners for providing that option. I made an attempt to buy Christmas presents for everybody with made-in-America items, but that was waylaid by the teenagers who wanted electronics and a new cellphone – neither of which were made domestically. When the older boy went off to his first college apartment and took his bed with him, we turned his room into a guest room and bought made-in-Galax Vaughan-Bassett Furniture from a local store. I know intimately now that there are real people and real livelihoods at stake at the other end of a consumer purchase. Continue reading →

Beth: The planning was the biggest undertaking — and by that I mean the three months it took me and my agent to get the book proposal, including a 27-chapter outline, into shape before submitting it to publishers. I followed that loose outline religiously, though some of the facts changed as my reporting turned up new details and twists. Having the rough outline storyboarded like that afforded me the opportunity to focus close-in on the chapter I was working on at the time, which was freeing. I had the entire outline written on

Beth: The planning was the biggest undertaking — and by that I mean the three months it took me and my agent to get the book proposal, including a 27-chapter outline, into shape before submitting it to publishers. I followed that loose outline religiously, though some of the facts changed as my reporting turned up new details and twists. Having the rough outline storyboarded like that afforded me the opportunity to focus close-in on the chapter I was working on at the time, which was freeing. I had the entire outline written on

This bottle tree was a gift from my mom to celebrate the launch of Dream Boy, my book with Mary Crockett, which is out today. Mary and I we were friends before, but our friendship was truly sealed in the pages of this book. There are so many ups and downs in publishing. Having a friend to share those with you? Pretty darn priceless!

This bottle tree was a gift from my mom to celebrate the launch of Dream Boy, my book with Mary Crockett, which is out today. Mary and I we were friends before, but our friendship was truly sealed in the pages of this book. There are so many ups and downs in publishing. Having a friend to share those with you? Pretty darn priceless!